History of the Company

The Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths received its first royal charter in 1327.

Founded to regulate the craft or trade of the goldsmith, the Goldsmiths' Company has been responsible since 1300 for testing the quality of gold, silver and, from 1975 and then 2010, platinum and palladium.

Henry III made the earliest attempt at regulating the standard of gold and silver wares, passing an order commanding the mayor and aldermen of the City of London to choose six of the more discreet goldsmith of the City to superintend the craft. The standards of fineness for gold and silver are also stipulated.

Edward I tries again to prevent frauds being committed by goldsmiths, passing a statute commanding that ‘no goldsmith… shall from henceforth make or cause to be made any manner of vessel, jewel or any other thing of gold or silver except it be of the true alloy […] and that no manner of vessel of silver depart out of the hands of the workers, until further, that it be marked with the leopard’s head’.

The ‘Guardians of the craft’ were to go from ‘shop to shop’ to assay work and apply the leopard’s head mark. Silver had to be of sterling standard (92.5% pure silver) and gold had to be of the ‘touch of Paris’ (19.2 carats). Goldsmiths outside London were also supposed to keep to the same standards.

In 1363 an ordinance of Edward III established the maker’s mark, which was now required alongside the leopard’s head. Each Goldsmith had a mark unique to them, identifying the goldsmith responsible for making a piece of plate.

The gold standard was lowered to 18 carats and the Goldsmiths’ Company was specifically made responsible for the ‘Keeper of the Touch’ and liable for penalties for his misdoings. The need to differentiate old and new plate caused by this change led to the introduction of a new mark, showing the leopard’s head with a crown.

Now the Company was liable for fines, caused by a Touch Warden marking wares below standard, a Common Assayer was employed. The Assayer would make assays at Goldsmiths’ Hall supervised by the Touch Warden on a weekly basis. It also led to the introduction of the date letter. This changed every year, and identified the Touch Warden responsible. Most of the main elements of hallmarking were now in place: the leopard’s head, the maker’s mark, and the date letter.

From this point onwards Goldsmiths’ Hall became the home of a permanent assay office, and it is probably from this that the term ‘hallmark’ originates.

The lion passant guardant (facing the viewer) began to be used as part of the hallmark. Although no official record survives to explain its introduction, it is possibly connected to the sudden appearance of two of Henry VIII’s men into the assay office in that year. The King had been debasing the coinage since 1542, and the Company had done something to incur his anger – in fact it was ordered to surrender its charter, a disaster only averted by his death in 1547.

The gold standard was raised to 22 carats, and the silver standard was confirmed as sterling. (18 Eliz. C. 15)

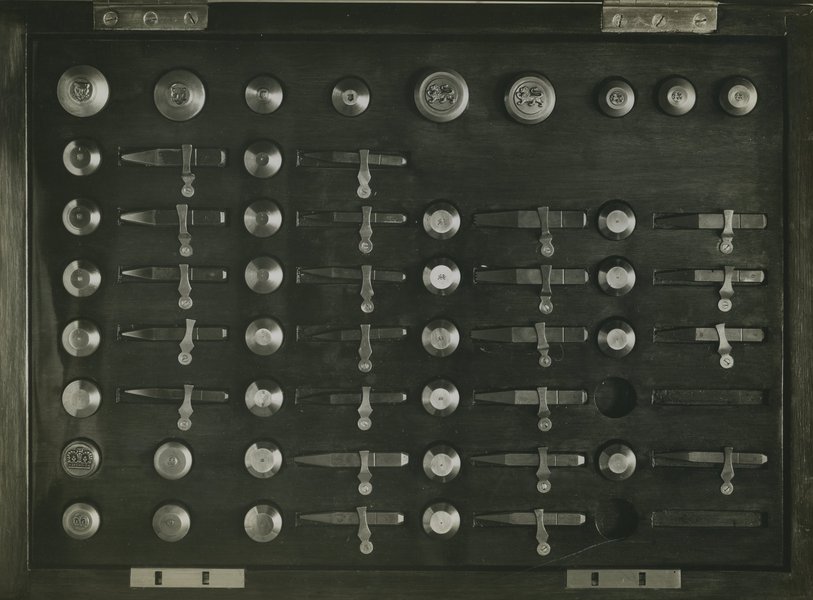

The Goldsmiths’ Company was appointed as one of the Keepers of the Troy Weight, the measurement of weight used for gold and silver. The nest of standard weights has remained in the Hall ever since.

Troy weights, 1588, brass with leather

The start of written records of the Trial of the Pyx, which had been carried out by goldsmiths since the 13th century.

The prosperity the country had enjoyed during this period meant that large quantities of silver coin were being melted down to meet the demand for silver plate. To protect the coins from the melting pot, the standard for plate was raised to 95.84 % pure silver. This was reflected in a change to the hallmarks, with a lion’s head erased and a seated figure of Britannia replacing the crowned leopard’s head and the lion passant guardant.

The format of the maker’s mark also changed, from initials or devices to the first two letters of the maker’s surname. By an anomaly, the only plate stamped with sterling silver marks throughout this period was gold, which never had separate marks.

By a statue to 1719 the old sterling standard was restored, but the Britannia standard remained as an alternative. However, a tax on silver plate introduced at this time meant that many goldsmiths – the ‘duty dodgers’ – went to great lengths to avoid getting their work properly hallmarked.

The reintroduction of the sterling standard had led to confusion over the correct format of the maker’s mark, with some goldsmiths using their initials, and some using the first two letters of their surname. To remedy this a statue ordered that all goldsmiths destroy their marks and register new ones at the Hall, using their initials and a new style of lettering. It was hoped that this move would also help to detect counterfeit marks.

Counterfeiting hallmarks became a felony, punishable by death.

The growth of large scale manufacturing and the use of machines for silver production in Birmingham and Sheffield led to a call for new assay offices in these cities. The Goldsmiths’ Company was opposed to this proposal, however a Special Committee of Inquiry set up by the House of Commons found in its favour.

An act of May 1773 established assay offices in Birmingham and Sheffield, and the Goldsmiths’ Company (whose own assay office was found to have committed some errors) was left to pay the not only its own legal fees, but those for the London trade as well.

Although the tax on silver imposed earlier in the century had proved difficult to collect and had been abandoned, a need to raise money prompted Parliament to not only re-impose duty on silver, but also introduce a new duty to gold. This necessitated a new hallmark, the sovereign’s head or ‘duty mark’. The direction the head faced changed from left to right in 1786.

Goldsmiths were allowed to reclaim the duty paid when the plate was exported, known as ‘draw-back’. To indicate that the draw-back had been paid, another mark, the standing figure of Britannia was introduced. However as it was stamped on finished goods there were complaints that it caused damage, and it was withdrawn in July 1785.

18 carat gold was reintroduced as an additional standard and given the marks of a crown and the figure 18. No marks were designated for the higher 22 carat standard, which continued to be struck with the same marks as silver. A remark found in an assay officer’s notebook indicates that from 29 May 1816 an additional mark of the ‘sun in splendour’ was also struck on 22 carat gold.

The leopard’s head mark lost its crown, and the lion passant ceased to be guardant and faced to the left. It is thought that the marks were changed, without public announcement, with the hope of catching out forgers.

22 carat gold was finally recognised with marks featuring a crown and the number 22. Continual worries about the forging of hallmarks were reflected in penalties laid down for the forging of dies and marks, the possession of fraudulent articles without just cause and making alterations to wares which had already been assayed and marked.

15, 13 and 9 carat gold were introduced, indicated by marks denoting their actual fineness. A year later gold wedding rings were made liable for hallmarking for the first time.

For the first time imported gold and silver items were identified with a special mark, and ‘F’ in an oval escutcheon (previously imported wares had been marked as if they were made in Britain). Over the next 40 years the marks used to indicate foreign plate changed frequently, making them particularly difficult to recognise.

The tax on gold and silver plate was at last withdrawn, and with it the sovereign’s head mark disappeared.

By an Order in Council the 15 and 12 carat standards for gold were cancelled, and substituted for one of 14 carats.

A voluntary mark celebrating the Silver Jubilee of King George V and Queen Mary was available to goldsmiths for two years between 1934 and 1935. Its popularity led to further commemorative marks: for the Coronation of H.M. Queen Elizabeth II in 1953 and 1954; for the Silver Jubilee in 1977; for the Millenium in 1999 and 2000; for the Golden Jubilee in 2002 and the Golden Jubilee in 2012.

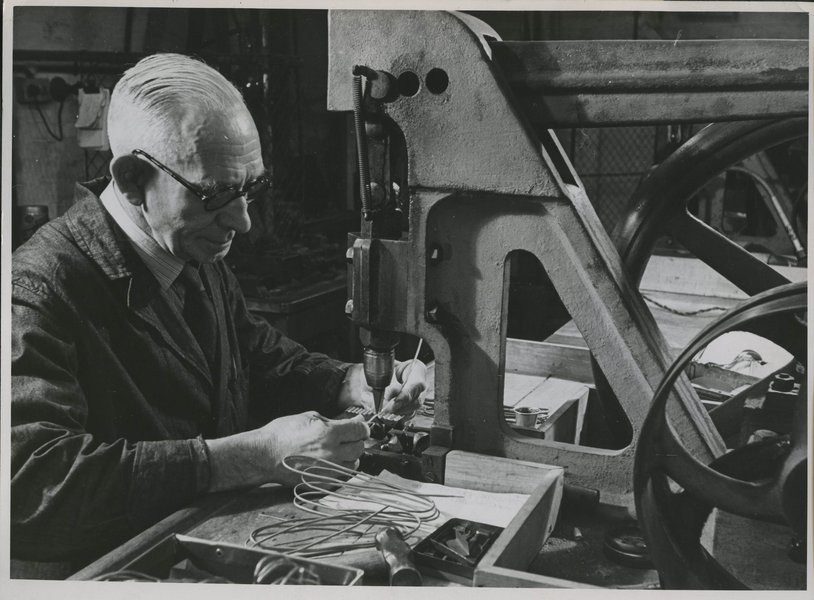

The Assay Office suffered bombing and was moved to Reigate, where, reduced to a staff of 11 they continued hallmarking throughout WWII.

Wartime measures also saw the introduction of a ‘utility’ mark, the result of a Board of Trade Prohibition of Supplies Order of 1942. This restricted the manufacture of gold wedding rings to 9 carats and a weight of less than 2 dwts. To show they had been produced by government authority they were marked with a special punch featuring two circles, each with a section cut out, similar to that used on utility clothing.

The Stone Committee on hallmarking recommended, inter alia, the closure of two of the six existing offices (Chester and Glasgow) and the repeal of previous legislation in order to make the law clearer and more easily enforced.

The problem of streamlining many centuries of hallmarking legislation to create an efficient and workable system had been considered by the Board of Trade for over a decade but in 1973 Royal Assent was given to a measure which repealed all existing hallmarking statues and consolidated them into a single Act.

On 2 January 1975 the new Hallmarking Act came into effect, including the introduction of marks for platinum, featuring an orb and a cross.

On 1 April the UK ratified the International Convention on Hallmarking, under which articles assayed at an authorised assay office in a member country and bearing special Convention marks can be accepted in another country without further testing. 1977 marked the celebration of 750 years since the Company’s first charter. A commemorative mark for the Queen’s Silver Jubilee approved for use on silver wares. The following year, an exhibition at the Hall celebrated the history of the Assay Office and its 500 years at Goldsmiths’ Hall.

In 1999, the usage of hallmarks changed to make the sponsor’s mark, the standard mark and the town mark being compulsory. The date letter and the other standard marks such as the lion passant became voluntary. New standards of gold, silver and platinum were introduced.

An amendment to the Hallmarking Act of 1973 made it possible to mark any combination of mixed precious metals and to allow some combinations of precious metals and base metals.

From 1 January hallmarking became a legal requirement for all palladium articles weighing over 1 gram.

A new satellite assay office was opened in Greville Street to serve Hatton Garden’s jewellery trade. Other successful sub-offices have since been opened, including one at Heathrow Airport in 2008 and an in-house assay office at Graff Diamonds in 2015 – the first within a retail jeweller.

Silver Bowl, by Elizabeth Peers, with the London hallmark.

The Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths received its first royal charter in 1327.

The magnificent Hall, opened in 1835, is one of London's hidden treasures

The Goldsmiths’ Company Assay Office is where hallmarking began, and we have been testing and hallmarking precious metals for over 700 years.