John Donald [1928-2023]

Dr Dora Thornton, Goldsmiths' Company Curator, celebrates the jewellery of John Donald in the Company Collection

The Company recently heard the sad news of the death of one of Britain’s greatest jewellers, designers and goldsmiths, John Donald. Born in 1928, Donald was an innovative and pioneering designer who understood twentieth-century concepts of fashion and glamour. He belonged to that select group of London-based makers who led the revolution in studio jewellery from the 1960s.

John studied at the Royal College of Art in London alongside Robert Welch and Gerald Benney, before setting up as a jeweller in London, opening his first workshop in Bayswater in 1960 before moving in 1968 to 120 Cheapside – a stone’s throw from Goldsmiths’ Hall – and opening an additional atelier in Geneva as his international reputation grew. John’s characteristic baroque style won him global acclaim, his work being especially prized in Kuwait and Japan. Royal patrons included HRH Princess Margaret, who was to become a friend as well as a major patron and inspiration. In partnership with Russell Cassleton Elliott, John co-authored Precious Statements, which was published in 2015, and to which I refer here.

John Donald’s work is well-represented in public and private collections. However, his principal patron was the Goldsmiths’ Company, which acquired twenty-eight of his jewels between 1958 and 2002. It is exciting to realise that as a result we have many of his rare, innovative early pieces in the Goldsmiths’ Company Collection - including some surprises - which as a group brilliantly document his career.

The Goldsmiths’ Company’s relationship with John Donald began during the difficult post war period, where he, like many young designers and craftspeople faced the challenge of both creating and selling beautiful, luxurious, wearable works of art at a time of extreme austerity. The 1961 International Exhibition of Modern Jewellery at Goldsmiths’ Hall - co-curated with the Victoria and Albert Museum by Graham Hughes, the Company’s dynamic Art Director and Curator - would become a turning point in the recognition and promotion of contemporary jewellery as an artform. In the late 1950s however, the after-effects of the diversion of metals and makers to the war effort was still being felt. Although food rationing was no longer in place, many people faced economic hardship, whilst a swingeing Purchase Tax on new luxury goods had reached 125% at its peak. John recalls in Precious Statements: “When I started in the mid-to-late 1950s, there were very few new things being made in jewellery…Innovation just hadn’t happened for 20 years, partly because of the war, so in design terms one could do anything at all. It was a completely open book.” Gold was out, so he started by experimenting with chenier bullion or tubing: “First I looked at all the products of the bullion dealers and then itemised them ie: round, square, oval rods; round, square, oval tubes and varying thicknesses of sheet metal. From these various forms I cut square rods, oval tubes at angles and into small pieces, beginning to make three-dimensional forms.”

Two leaf brooches in the Goldsmiths’ Company Collection are rare surviving examples of this early work, one in silver-gilt made from angled tubes formed into a leaf can be seen in fig.1, the other is cut from oxidised silver sheet with triangular shaped blades set as a 3D leaf form.

fig.1 - Brooch, 1958, by John Donald. The Goldsmiths’ Company Collection.

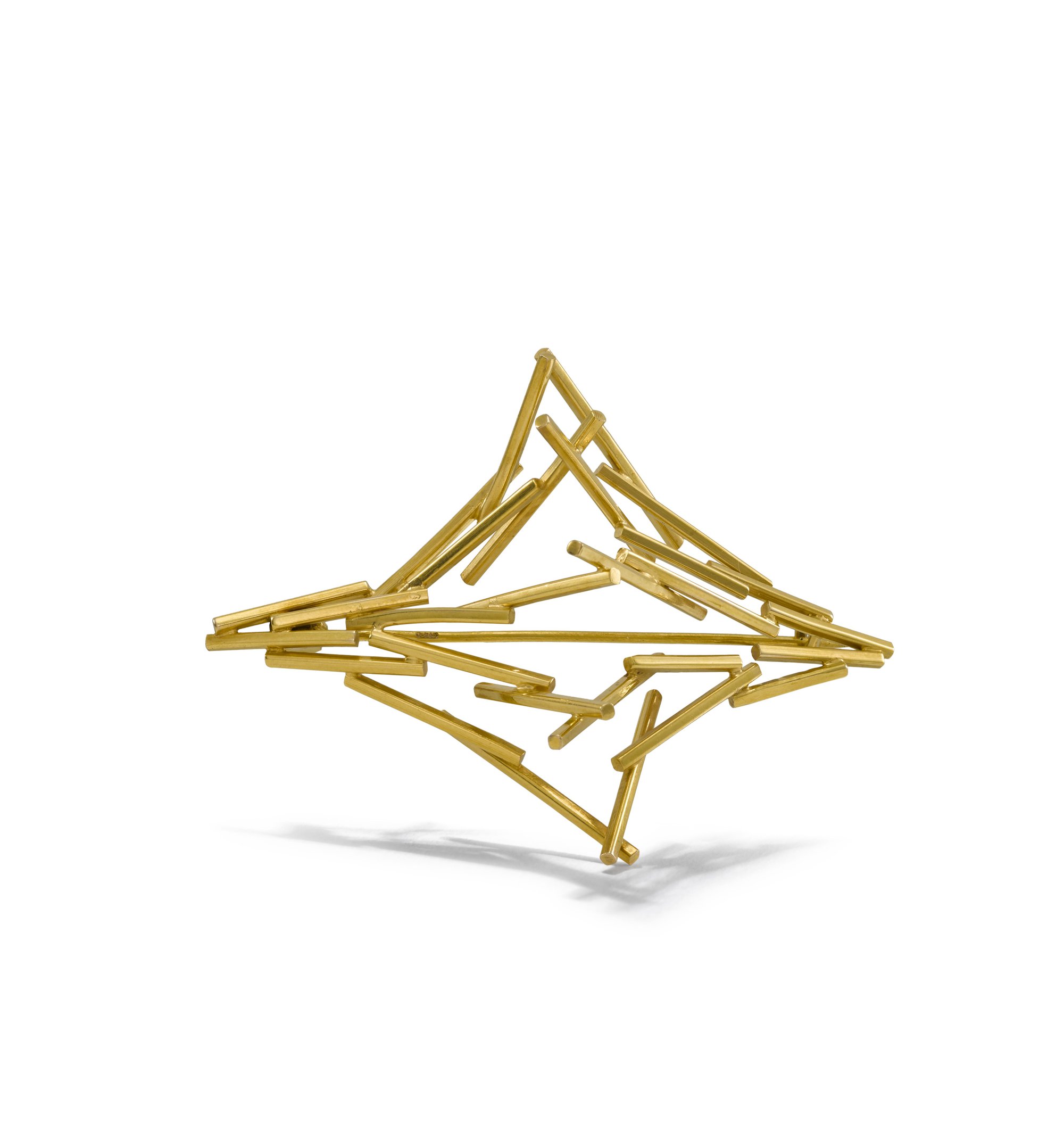

Another uses 9 carat gold wires and tubes of bullion cut into different lengths and soldered to create a 3D star [fig. 2], a fantastic example of John's early experiments with geometrical form.

fig.2 - Brooch, 1959, by John Donald. The Goldsmiths’ Company Collection.

This series of brooches from the late 1950s were John’s response to a design challenge set by Graham Hughes: “...I returned to my work bench to approach the three-dimensional problem of jewellery, intending to achieve a new concept in the forms of metalwork. Some of these designs were then bought for the Company’s Collection. As one can imagine, this was an enormous boost to my confidence and, of course, gave me a small amount of money with which to continue experimenting.”

In 1959, Donald won the design competition for a new Warden’s badge—a heraldic piece in a modern idiom with an abstract irregular textured rim [fig. 3].

fig.3 - Warden’s Badge, 1959, by John Donald. The Goldsmiths’ Company Collection.

This was followed in 1960 by a special commission, to make a Court Wine Cup [fig. 4] for the distinguished physical chemist and Nobel Prize Laureate, Sir Cyril Hinshelwood.

fig. 4 - Sir Cyril Hinshelwood's Court Cup, 1960, by John Donald. The Goldsmiths’ Company Collection

The Cup is unusual for the period of its creation, in that it was both designed and made by the same individual, a jeweller at that. It has a silver spun bowl with a gilded interior, with the stem cast from sterling silver with a crisscross pattern running towards the foot. Engraved on the front of the cup is the Goldsmiths' Company crest within an oval lozenge, with Sir Cyril’s arms on the other side. As a work of art, it is distinguished by its simplicity and by its perfect balance in the hand.

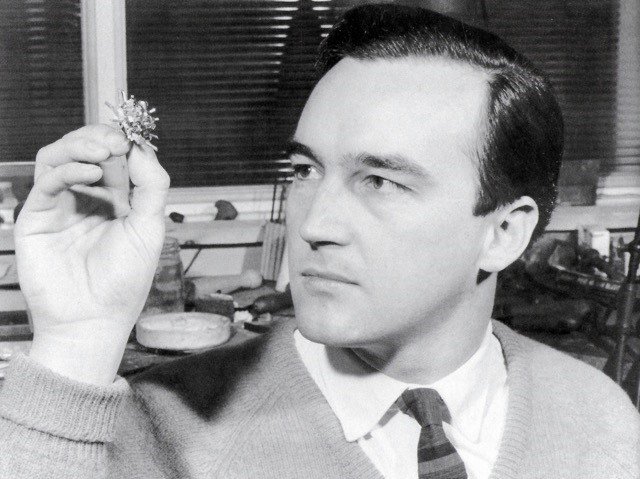

Brooches however take us to the heart of Donald’s creativity and skill. A photograph from around 1952 [fig. 5] shows him holding one of his early brooches set with iron pyrite - perhaps the very one in the Goldsmiths’ Company Collection.

fig. 5 - John Donald, 1962. Credit: John Donald and Russell Cassleton Elliott

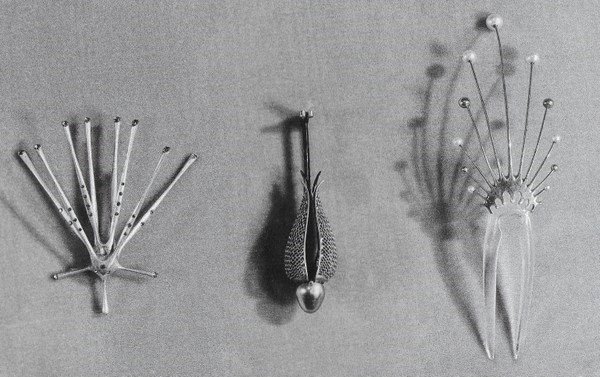

In a sense John grew up with brooches, writing in Precious Statements about being fascinated as a child by a peacock brooch that his mother liked to wear. His first jewel, made in 1952, was a silver brooch set with pastes in the form of a pencil sea urchin [fig. 6 - to the left of the image] which he had seen at the Natural History Museum - the collections of which supplied a source of continued inspiration throughout his career as a jeweller.

fig. 6 - Three brooches, (1952-53), John Donald. Credit: John Donald and Russell Cassleton Elliott

He also drew inspiration from the past, having a particular affinity with then deeply unfashionable Victorian jewellery. An early research visit to Italy allowed him to visit cathedral treasuries, where he admired Baroque church silver—especially monstrances with their radiating bejewelled designs; precious display pieces to show wafers consecrated during the Catholic Mass. He recalled their aesthetic in a brooch made in 1963, with a sunburst of gold spokes set with synthetic rubies [fig. 7].

fig. 7 - Brooch, 1963, by John Donald. The Goldsmiths’ Company Collection.

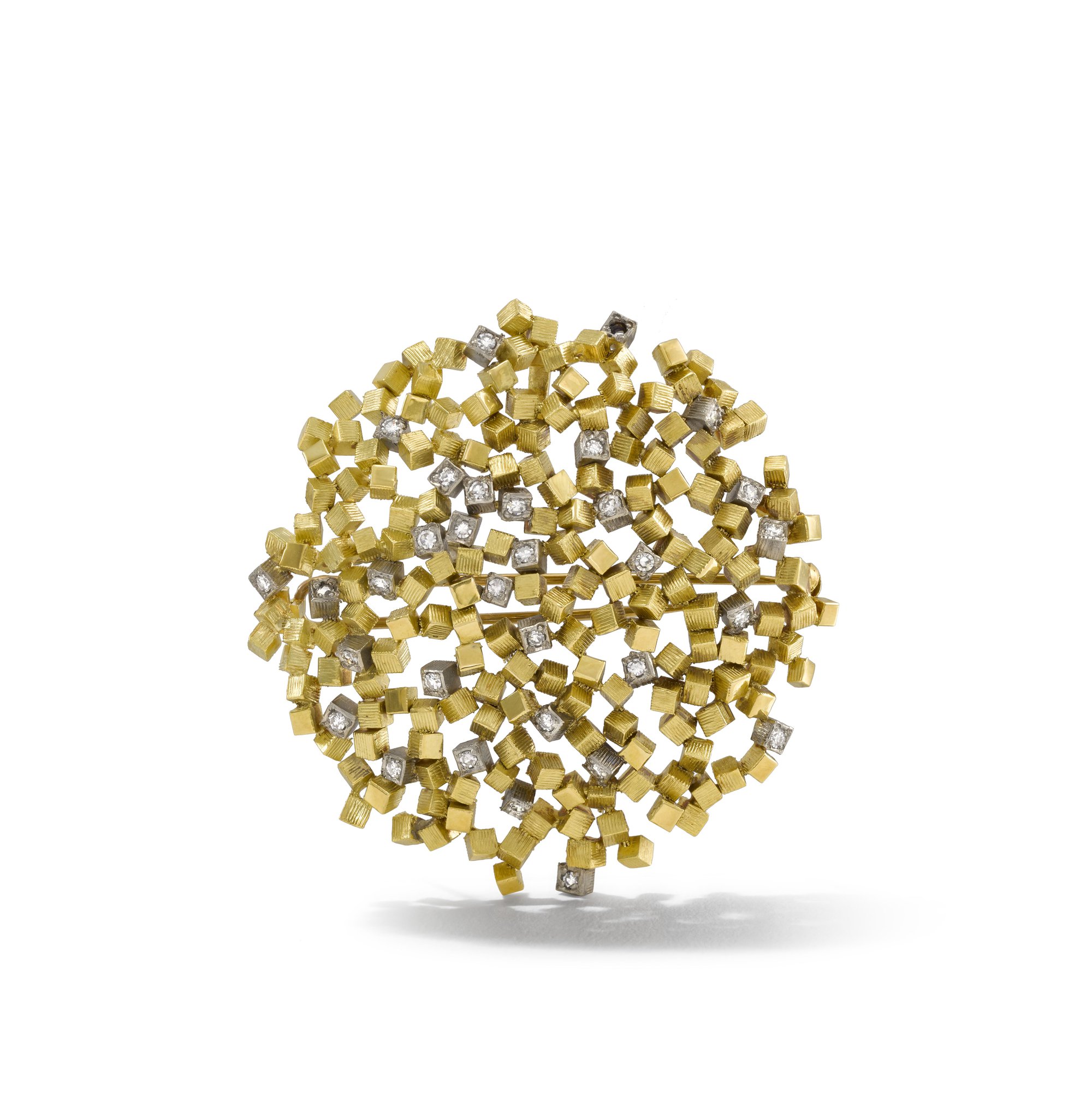

His brooches from the 1960s were artistic statements. As part of the research for an exhibition, later a book, The Brooch Unpinned, I wrote to him and his wife Cynthia to ask what it was about the brooch as a form that appealed to him. John’s answer revealed his creative vision as an artist: “Designs were always experiments in form; small sculptures or three-dimensional painting. In the early days, there were times when I thought to supply an appropriately sized picture frame where the brooch could be pinned and viewed as pure artwork, without reference to or influenced by the wearer.” When I asked about the special challenges of designing brooches, his reply was no less thoughtful and revealing: “When designing specifically for clients, I would take into account their personal details such as colouring, size and personality. Often, they would either choose from style and texturing of existing gold work or they would be happy for me to go through the drawing/design process, which also then led to a model being made before the final decision - of course, at this stage, the size of stones etc. could always be altered and a final costing reached.” No wonder that brooches by John Donald only rarely appear at auction, their owners cherishing them as modern classics, which remain wonderfully wearable. The aesthetic of his 1962 diamond brooch [fig. 8], perhaps the iconic jewel of the 1960s, still resonates with contemporary innovators such as Jo Hayes Ward, translated into a contemporary idiom using the latest technology.

fig. 8 - Brooch-pendant, 1963, by John Donald. The Goldsmiths’ Company Collection.

John Donald’s influence on other makers has always been liberating. Jacqueline Mina believes herself fortunate to have had a summer job working for him as a student in 1964, which taught her to work directly into precious metal “in an uninhibited and experimental way”. She now thinks that her brief but illuminating experience of Donald’s workshop taught her more than her three years as a student at the Royal College of Art. It deepened the impact made on her by the 1961 International Exhibition of Modern Jewellery, which showed her “what jewellery could be.”

Rings in the Goldsmiths' Company Collection show John’s innovative approach to design and making. The ‘Drum’ ring [fig. 9] - which matches striking contemporary design with exquisite artisanry - developed from his first trial pieces using what he called “nugget flakes”, formed by dropping molten gold into cold water. To make the crown of this ring, he soldered the flakes together into a sheet, then rolling the sheet to form a circle. The shape of the crown demanded that the marquise diamonds had to be set deep into the hollow centre, making the setter’s work extremely difficult.

fig. 9 - ‘Drum’ ring, 1963, by John Donald. The Goldsmiths’ Company Collection.

Donald explains in Precious Statements: “I solved this problem by adding a thread to the very fine stone set wires, then screwing them into the inside of the crown. This was very time-consuming, and it was difficult to reach a good design balance. It did achieve the three-dimensional effect which I had had in my mind.” Experience of using this method showed him that he could set the stones on the wires before soldering them into the crowns, protecting them from the heat. The result, something completely new in ring design, became an iconic form for the artist.

John Donald proved his affinity with baroque pearls through the variety of gold settings that he designed, aimed at enhancing their irregular form and lustre. He first started exploring Scottish freshwater pearls from the River Tay in 1959, as seen on a delicate ring fit for a mermaid, set with nine small rubies and two bubbling greyish pearls in nuggeted gold [fig. 10].

fig. 10 - Ring, 1959, by John Donald. The Goldsmiths’ Company Collection.

Another ring from 1960 of uncompromisingly modern design is set with a square peridot in a split gold shank which fans out like turbine blades around the stone [fig. 11]. While on a third, an iron pyrite is held in three irregular gold claws, to show off its allure as traditional `fool’s gold’. All three pieces exemplify his love of asymmetry and organic texture.

fig. 11 - Ring, 1960, by John Donald. The Goldsmiths’ Company Collection.

We recently rediscovered, and identified a bracelet [fig. 12] in the Goldsmiths’ Company Collection as an example of John’s student work, made in his third year at the Royal College of Art. It is made of inexpensive materials - simulated white opals, silver and nickel - but each element is ingeniously designed and made to form a bracelet, which curves to the wrist. Even the toothed edges of the links are curved upwards, so as not to snag the skin or delicate clothing.

fig. 12 - Bracelet, c1956, by John Donald. The Goldsmiths’ Company Collection.

The gilded collets mirror the opals and the interlocking links, whilst the catch works well. It was Joanna Hardy, jewellery historian and special adviser on our Contemporary Craft Committee, who thought of asking John if the bracelet might be by him. Cynthia Donald wrote back excitedly on behalf of her husband, explaining that it was indeed his, and that he had thought the piece lost.

I was delighted to recognise the bracelet in John’s Christmas advertisement from 1962 [fig. 13] - published by Graham Hughes in his history of jewellery in 1963 – and see yet another connection between John and the Company in his formative years.

fig. 13

John Donald’s death marks the end of an era. In the words of Joanna Hardy, `His work is a wonderful example of innovation, freedom of thought and expression. It is a time capsule representing an era spanning five decades since the 1960s that British jewellery can never witness again.’

[Quotations used with kind permission from John Donald and Russell Cassleton Elliott, Precious Statements, Carmarthen 2015, and from personal communications with John and Cynthia Donald.]