Mark Nuell: Modern Lapidary by Joanna Hardy

First appearing in the Goldsmiths' Review 2020, this is the story of goldsmith, jeweller and lapidary Mark Nuell.

When an item catches my eye, it is usually because it is well made and of original design. Reaching this level of craftsmanship takes years of perseverance, determination and the desire to push technical boundaries. Skills and design will keep evolving in talented craftspeople, and their journey of creativity and struggle is integral to their pieces.

Regular visitors to the Goldsmiths’ Fair are familiar with many of the exhibitors and their methods; as a result, when a goldsmith or silversmith proudly displays a new departure in their technique or design, it is a moment of great excitement for a collector. Sensing these changes is what makes meeting the maker in settings such as the Fair so important. Being able to ask questions about how their work is crafted and how it has evolved is crucial in appreciating what has gone into that piece.

Aquamarine earrings, 2019, aquamarines cut by Mark Nuell, 18 and 22ct gold

Last September at the Fair, one such craftsperson, Mark Nuell, particularly caught our attention with two of his sapphire rings. Asking Mark to explain them in more detail opened a dialogue that allowed us to understand the journey that led to their creation. The conversation not only resulted in the purchasing of the two rings for the Goldsmiths’ Company Collection, but it also prompted me to visit Mark’s workshop in Cockpit Arts to learn more.

Born in the UK in 1961, Mark moved with his family to Australia two years later as part of the ‘Ten Pound Poms’ scheme, an initiative through which families paid £10 in processing fees to migrate to Australia. They travelled by plane (with about 10 stopovers) and settled in Brisbane, where they built a house. Mark’s father, Mike Nuell, got a job in an oil refinery, but at the weekends he would pack up the car and go off into the bush with a few mates fossicking for opals and garnets – a welcome relief from the grind of night shifts.

Aquamarine Ring by Mark Nuell

Mike heard about an area of sapphire deposits in Rubyvale, some 450 miles north-west of Brisbane. It was too far away for a weekend trip, so he decided to take the family on a three-week holiday. Mark, aged eight at the time, remembers the trip being an adventure: “the roads were not tarmacked and we would get constantly bogged.” When they arrived, his father spent his days fossicking for sapphires, showing the family what he had found in the evening. Mark recalls sitting on the ground, picking up little green and yellow sapphire crystals, and putting them in a matchbox, totally fascinated.

On that holiday, his father found a few sapphires that he was able to sell in Brisbane. This success obviously gave him the impetus to give up his job, as, six months later, the family headed back to Rubyvale. Mike built them a corrugated tin shack on a hill called Reward, where they lived for months. There was no electricity or running water and the “dunny” was 100ft away, but that didn’t seem to matter: they just got on with the adventure. Mark, his brother and sister went to school in Anakie. It was 6 miles by car followed by 12 miles by school bus, and situated on the edge of a railway track that saw a train heading into the Outback once a week.

Mark cutting a stone

Mark remembers people were scattered throughout the bush, living in makeshift camps, caravans and huts, all hunting for blue crystals. The area attracted colourful characters who wanted to escape the monotony of city life. “They all had big hats and long beards and fancied themselves as prospectors; there weren’t any geologists, just a bunch of fossickers, like mudlarks, very hill-billy, without any real structure.” It was the early 1970s and dealers from Thailand set up their huts in Rubyvale to buy the blue sapphires the miners found. They were not interested in the greens and yellows, so the miners kept those for themselves. The sapphires were mainly discovered in alluvial deposits, but there were also tunnels and shafts made to a depth of up to 30ft.

Mark’s father eventually made some money from his ventures, which meant that he could afford a more permanent home further out in the bush. He bought an old timber house, put it on the back of his truck and used it to build the bush-timber house where they lived for the next 10 years. With his mining partner, he bought a digger and a jigger, which used water to separate the gravel and gems.

Mark remembers his childhood fondly as a very special time when he and his siblings had the freedom to run around and explore the bush. He had a pet emu, called Manni, and a bush pig, called Jackie pig. Yet, without really noticing it, he was also growing a deep understanding of and appreciation for sapphires.

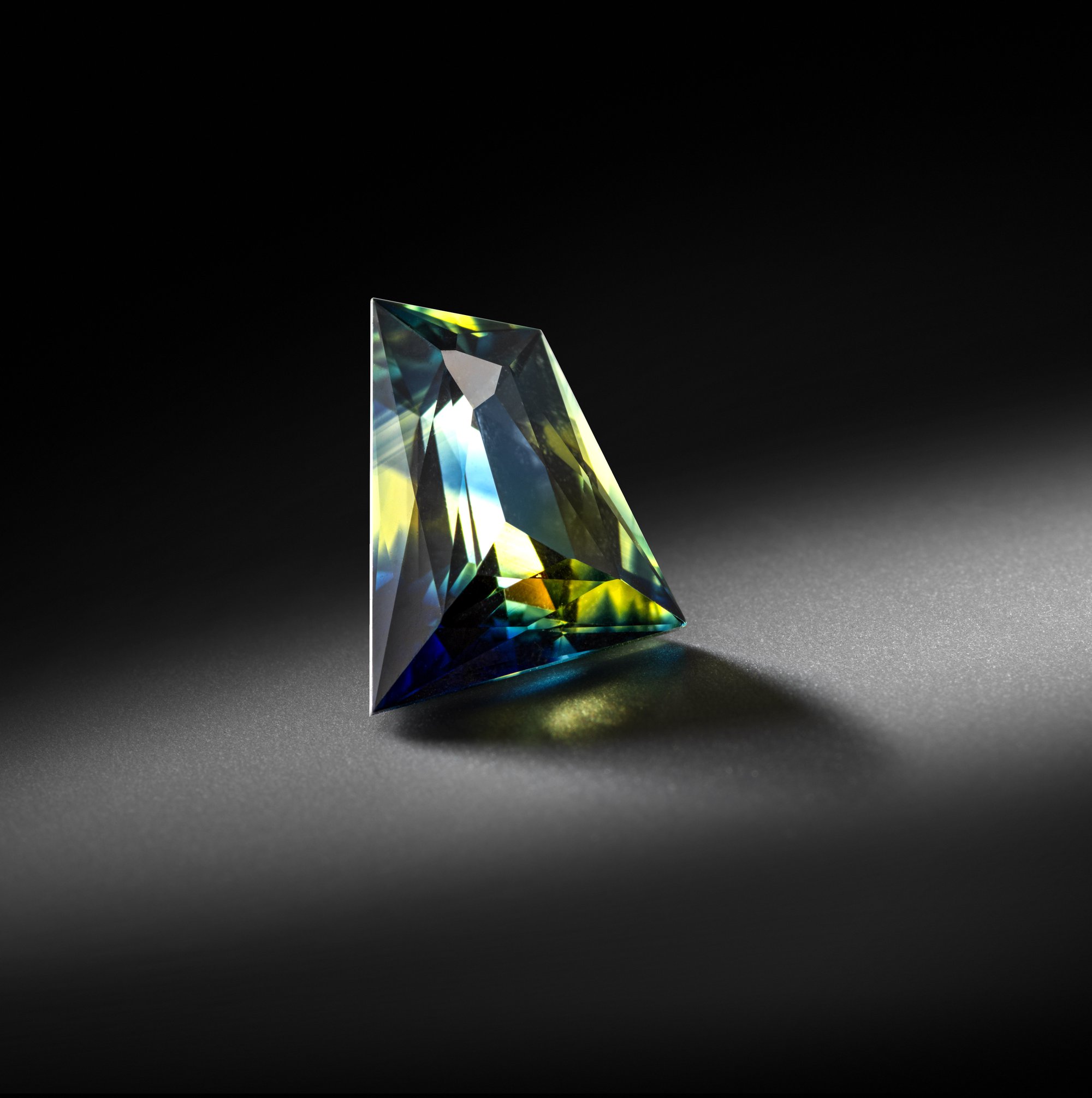

Cut sapphire

Amongst the European settlers were a couple of cutters from Austria, who faceted the sapphires unwanted by the Thai dealers for the miners. When Mark left school at 15, he joined them as an apprentice and stayed for seven years before setting up his own cutting business when he was 22. It felt a natural progression to learn how to become a goldsmith. At 24, he went to Sydney and was accepted onto a three-year course at a technical art college in Paddington, whilst still occasionally cutting stones to bolster his meagre income.

After finishing college in 1990, he was lured to London and sold his cutting machine to help pay for his passage. As a result, Mark did not cut a single gemstone for the next 28 years. Armed with only his college portfolio, Mark showed his drawings to galleries until avant-garde Electrum offered to sell his work. He had to find a studio pretty quickly to make the pieces!

Mark’s father passed away in 2017 and his mother wanted to give him something in memory of his Dad. Mark asked for a cutting machine, as he had been thinking about new ideas, inspired by the German gemstone cutter Bernd Munsteiner.

There are not many gemstone cutters who are also accomplished goldsmiths and this rare combination allows Mark freedom of thought and the ability to avoid being restricted by conventional techniques. Sitting in his studio, he shows me his latest piece: a necklace to be set with twenty-three aquamarines, all cut by Mark. The faceting of each stone is dictated by the shape of the rough crystals, which – in an example of how trading has changed – he bought from Nigerian dealers after finding them a few years ago on the internet. Unlike traditional cuts, there is no table facet and the reverse is also faceted, allowing the light to dance and bounce through the sea-green gems. Mark is taking his time to feel what is right for the necklace and the stones, so as to bring out the gems’ maximum potential, drawing on an intuition developed during his childhood in the Outback.

Two Rings by Mark Nuell, Goldsmiths' Company Collection

The two rings that are now part of the Goldsmiths’ Collection are set with sapphires that Mark chose on his most recent trip to Rubyvale, where he still buys gems from family friends. Sapphires come in all colours, but, as with the Thai dealers of Mark’s childhood, commercial demand is almost exclusively for blue. The majority are heat treated to achieve a uniform colour throughout the stone, but, refreshingly, Mark cuts sapphires to display the natural beauty of yellow-, green- and part-coloured gemstones, which have not been tampered with by man.

Mark’s jewellery is a result of a wealth of influences and factors: learning to be comfortable with nature as a child; a sense of freedom; guidance from his parents; his artistic talent. All these accumulate in jewels that have integrity and honesty, which cannot fail to bring the wearer pleasure and happiness.

This article first appeared in the Goldsmiths' Review 2020 - follow the button below to read more and download