Tackling Diversity one Bright Light at a Time by Melanie Eddy

In this article, Melanie seeks to reframe the historic underrepresentation of designers and makers of black heritage in the goldsmithing industry, and to acknowledge the significant contributions they have made.

In line with the global civil rights movement sparked by a spate of despicable killings due to police brutality in the US, people across the world have been recognising the structural and systematic racism inherent in many of our institutions. Organisations have been reviewing their efforts to address diversity, equity and inclusion, and jewellers, silversmiths and those in the allied trades are no exception. An incredibly high percentage of the resources that are used in this sector is sourced and processed by brown and black people around the world but we are not the face of this industry.

Gold from Mali and the Akan/Asante kingdoms could be accessed via the Ghanian coast, bypassing routes across the Sahara. It is not for nothing that present-day Ghana was formally known as the Gold Coast under Colonial administration. British-Ghanian jeweller Emefa Cole, a London Metropolitan graduate, recently travelled to Ghana after having been granted permission by the Asantehene to learn the ancient traditions of goldsmithing in the Ashanti Kingdom, under the supervision of the royal goldsmith, Nana Poku Amponsah Dwumfour. She returned to the UK just as airports were closing due to the Covid-19 pandemic. She states, “The Goldsmiths of West Africa are incredibly skilled craftsmen – their intricate creations have been looted in punitive expeditions over the centuries…[and] adorn the display rooms of many museums in Europe and America; their techniques replicated and their culture appropriated without being afforded due respect and credit.” Her Erosion collection, inspired by childhood tales of golden nuggets unearthed by heavy rainfall, alludes to the history of small-scale, alluvial agriculturalist mining of widespread placer deposits across West Africa.

Selection of rings and bangle, by Emefa Cole

Prominent silversmith, RCA graduate and Liveryman of the Goldsmiths’ Company, Ndidi Ekubia, whose work features in the Company’s Collection, freely acknowledges that her African heritage has deeply influenced her work. This combined with the mix of cultures she encountered growing up in industrial, inner-city Manchester. Stories and dialects from her mother, grandmother and extended family from southern Nigeria, western Nigeria and Benin have impacted her approach to making. The vibrant, ebullient nature of her home life has come through in the confidence with which she expresses emotion through the hammered metal vessels she creates. The movement and life visible in these pieces evoke the hammer strokes used in raising her objects. Early on in her career, she felt an impetus to tone down her voice – to blend in – for fear she would be misunderstood because her approach was different culturally to that of many of her contemporaries. It was through international exhibitions, meeting other artists from African backgrounds, and her long history of outreach work in libraries, schools, cafés and museums – taking her silversmithing and demonstrations, literally, to the people, often unpaid – that she gained confidence and felt at home with her voice.

Ndidi Ekubia, Liveryman of the Goldsmiths' Company

The exploratory and intuitive nature of Simone Brewster’s multi-disciplinary design and artistic practice means her output traverses a number of mediums from painting, to large-scale sculptural furniture, objets d’art and jewellery. It was her fascination with making and her memories of workshop making that took her from her work in architecture, upon completing Architecture studies at UCL, back into education for an MA in Design Products at the RCA. The freedom and fluidity that has defined her practice is also typified in her approach to learning and acquiring the skills necessary to support her aims and objectives. As a curator of shows, which often support diversifying the narrative in design, she says she has experienced a backlash from those who didn’t think those platforms were needed or necessary. Jewellery came to her swiftly upon graduation, first in wood and then in precious metals as she supplemented her design education with practical courses and diplomas to support this direction in her practice. Seeking to see how simple stacking shapes and forms could be used to construct adornment, she discovered how to develop simplicity into something complex and beautiful.

Portrait of Simone Brewster with sculpture Giraffe

The conversations that emerged in the research for this article have been truly enlightening. I was very lucky to be put in touch with two jewellers working at the height of their craft, whose stories the Goldsmiths’ Company will be exploring in detail in the near future as part of its Goldsmiths’ Stories initiative. Trevor Davis, a child of the Windrush generation, comes from a legacy of jewellery. His father, Keith Davis, reached the pinnacle of his craft here, working at David Morris in the 1960-80s before relocating to the US to work as a jeweller for Harry Winston. Trevor was in the workshop as a boy and then spent 12 years of his young life working in the trade in Trinidad before returning to the UK. He didn’t find the industry overly welcoming upon his return but, through the Prince’s Trust and mentors like Marcia Lanyon, he stayed the course, steadily progressing but not without challenges. Rudi Thomas, a diamond mounter, worked for 18 years at David Morris before joining the team at Graff. He has been there for 15 years. He has had an interest in jewellery from the age of 13, going straight from college to an apprenticeship with John Ringer of Dyer & Ringer. His passion for the trade burned so intensely when he left college that it took a long time for him to take on board the realities of what it meant to be a black man in this industry. There is a tinge of sorrow when speaking to Trevor and Rudi of a destiny disrupted – exemplary craftsman, with their skills recognised but not always acknowledged or reflected by the industry’s treatment of them. There is a sense that the dreams of their youth, of all that was possible for them, have faded into the background.

Trevor Davis in his studio

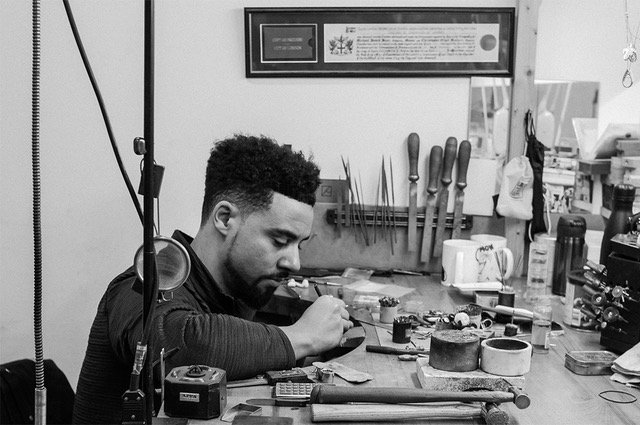

One young jeweller moving from behind the scenes into the spotlight is Ryan Nelson. Now a Freeman of the Goldsmiths’ Company following a five-year apprenticeship with David Lawes, he spent a further three years honing his craft before setting up his own studio. He hails from a family legacy of jewellery, his father Michael Nelson having been a jeweller and workshop manager for the Criton Group. Serving private clients as well as the trade, he is steadily developing fine jewellery collections and moving into new aspects of the retail market beyond the bespoke. Whilst acknowledging the challenges one can face as a jeweller of colour, he is resolved to succeed and his positive outlook is what is most apparent in any discussion with him. Mostly, he sees the problem as one of perception: the difficultly in establishing trust, in an industry where trust is essential to progress; the reluctance to build lasting professional relationships; the acknowledgment that it can be harder for people to buy into you as legitimate. His optimism is infectious and he says people think he is lucky, but I have a feeling he makes his own luck.

Ryan Nelson, Freeman of the Goldsmiths' Company, in his London Workshop

Whilst there have always been efforts from within black jewellery communities and amongst jewellers and silversmiths of colour to give back, these attempts are gathering momentum now and becoming more formalised as they receive wider support. Jeweller Kassandra Lauren Gordon followed up her open letter to the jewellery industry in June, which highlighted how current practices and systems limit accessibility and entry into the trade for black people, with a fundraising drive to set up a hardship fund to provide financial support to black jewellers and micro-businesses in the wake of the Covid-19 crisis. The Goldsmiths’ Company is collaborating with Kassandra both on the administration of the hardship fund, the Kassandra Lauren Gordon Fund, and on delivering one of the UK’s first social-research projects into the experiences of black British jewellers.

The barriers black people face regarding having access to and sustaining a career in the industry are serious, as are the experiences of those from other BAME communities. Information on the shocking salary disparity for those employed alone warrants a separate investigation. I think it is the erasure of the efforts and excellence of those that have managed to sustain practices and successful careers that is most insidious and detrimental to effecting positive and lasting change. Despite that, the resounding narrative from the people I have spoken to is not one of barriers to progress and struggle but of success, steadfast resolve and determined strength of character.

Simone Brewster, Cuboid Ring and Crystal Ring

All of those I spoke with have a genuine love for this trade and industry, which has enabled them to stay the course. Their ability to lead a creative life and share that with others is seen as a blessing. As Rudi Thomas states: “Jewellery has given me a good life.”

My jewellery career, in Bermuda, began in a small but well-equipped and highly sought-after local jewellers, The Gem Cellar, under the tutelage of a very talented black jeweller and business owner. Chet Trott was my route into jewellery and I can’t say for certain that I would ever have entered the trade had it not been for his support and guidance of my tentative and fledgling dreams. You cannot be what you do not see. Diverse businesses and organisations outperform their counterparts, with greater sales revenue, an increased customer base and higher profits. If we are to encourage and support those entering the trade from diverse backgrounds, we need to learn how to cast a longer and wider spotlight upon those markers of success and excellence that serve as role models and points of reference for those who will lead the charge as this industry moves to a closer reflection of the society it serves.

* The jeweller Melanie Eddy trained in Bermuda, Canada, New York and London. She holds an MA Design: Jewellery from Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design, where she is also a lecturer. A director of the Association for Contemporary Jewellery and a licentiate (with distinction) of the Society of Designer Craftsman, she has undertaken a residency at Turquoise Mountain’s Institute for Afghan Arts and Architecture in Kabul, Afghanistan, in the course of her career. She is based at the Goldsmiths’ Centre. Melanie is part of the Jewellery Futures Fund initiative, which seeks to address the systemic challenges faced by black jewellers through a matrix of support and resources.

This article first appeared in the Goldsmiths' Review 2020 - follow the button below to read more and download