Where Gold is King

Emefa Cole reflects on her pivotal experience as an apprentice in Ghana to the Asantehene's leading goldsmith for the 2021 Goldsmiths' Review.

By Emefa Cole

When I think of Ghana, the country of my birth and early years, I have vivid memories of a childhood spent in awe of nature. It was a beautiful introduction to an environment rich with diverse plant, insect and animal life, and a fascinating cultural history.

One piece of folklore I’ve never forgotten is about people in the Ashanti region discovering nuggets of gold on the ground, washed to the surface after heavy rains. It may sound like the stuff of fantasy, but Ghana is literally the land of gold, as the country’s earth is rich with this coveted, alluring metal.

Ghana is made up of numerous ethnic groups, one of the largest being the Ashanti (also known as Asante), a subgroup of the Akan. Their kingdom is built on soil blessed with gold, a great source of wealth and power to them. Gold represents the essence of the sun and symbolises life’s vital force – its soul. The importance of gold to the Asante is present in all aspects of their existence, most notably The Golden Stool, which has its own throne and is believed to house the spirit of the Asante people – those who have lived, died and are yet to come.

Kotoku Saabobe by Nana Poku Amponsah Dwumfour and Emefa Cole, 2020. Photography: Richard Valencia

Not surprisingly, due to the abundance and importance of gold to the Asante, their goldsmiths have an undisputed reputation as some of the world’s best. Their unparalleled skill in lost-wax casting can be seen in jewellery, décor created for rulers and the brass weights made for measuring gold dust; this precious dust was local currency until 1901.

I have been curious about Ashanti lost-wax casting since my days studying jewellery at London Metropolitan University and it was my wish to learn this special method for many years.

This wish became reality after I was granted permission by the Asantehene (overall King of the Asante) to undertake an ongoing apprenticeship under the supervision of his goldsmith, Nana Poku Amponsah Dwumfour. My trip was supported by a generous bursary from the Artists Information Company, and I was determined to embark on this journey despite the pandemic and looming uncertainty, fuelled by excitement and the possibilities of what lay ahead.

Heading out of the bustling coastal city of Accra towards the dense forest belt, we passed many stalls selling traditional earthenware and seasonal crops along the scenic route. Three and a half hours later, we arrived in the Garden City of West Africa, Kumasi – the seat of the Asante, one of Africa’s great imperial powers.

Words of wisdom rendered in brass by Nana Poku Amponsah Dwumfour. Photography: Richard Valencia

There we met one of the King’s men, who took us to see the Master Goldsmith in his traditional workshop. Nana and his ancestors have used it for generations to create some of the most exquisite, hand-sculpted artworks of gold, many of which are currently on display in museums around the world. I was warmly welcomed into this historically significant workshop, which still has the ancient furnace Nana’s ancestors used.

It was humbling to be in the presence of the guardian of this ancient craft so unique to the region. The Asantehene’s goldsmiths are admired around the globe for their ingenuity and technical sophistication, achieved using what appear to be very basic tools and materials. However, as I saw, the technique is far from simple. It requires great expertise, precision and patience to produce the desired results.

The process, which is handed down from father to son, is a true labour of love. In addition to the actual methods, the King’s Goldsmith must also be well versed in the proverbs these pieces represent, which may connote rank, wealth, bravery and power, as well as embodying warnings to enemies and lessons of morality. They preserve oral history and wisdom that is passed on through a combination of proverbs, maxims and riddles.

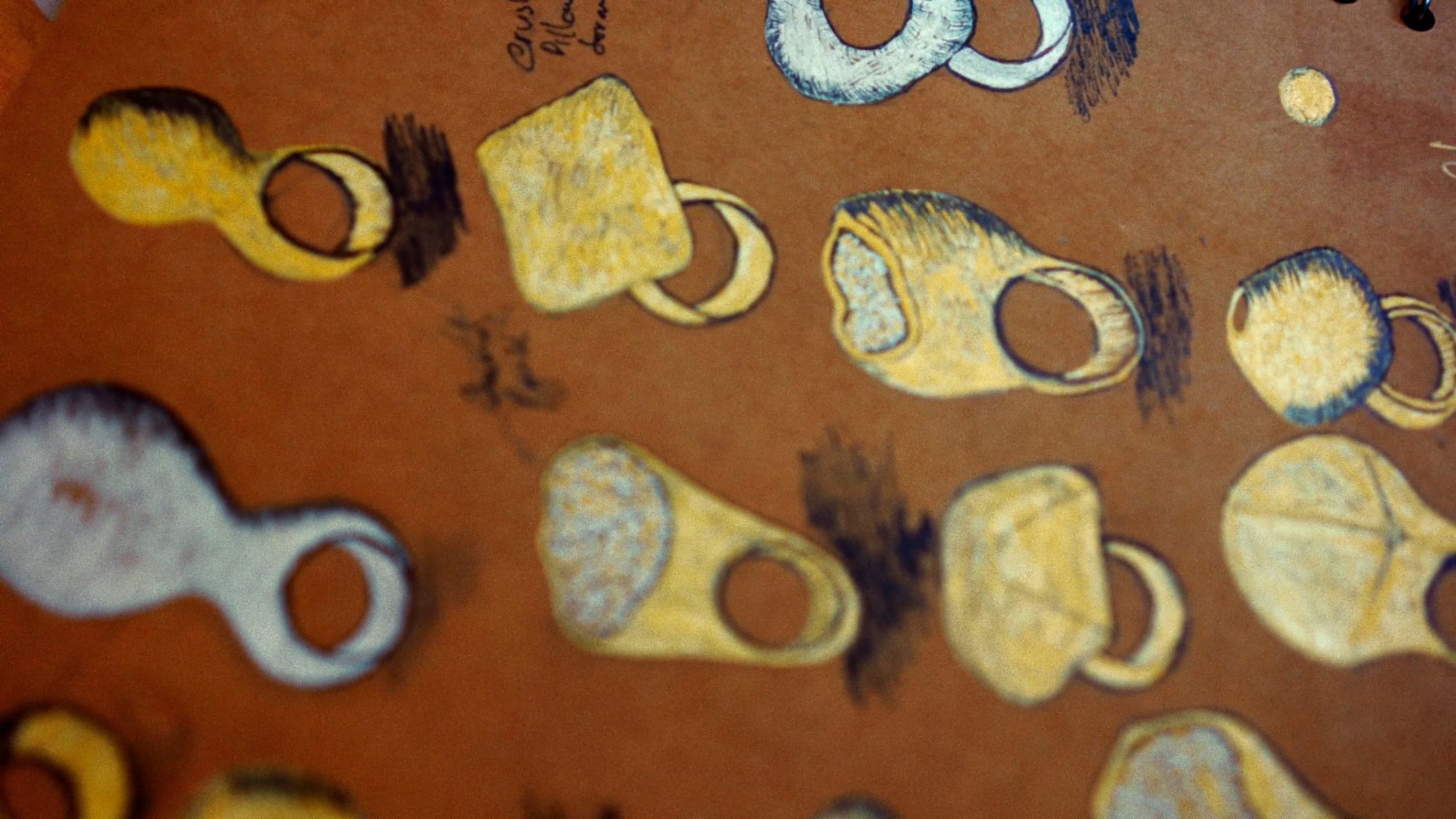

Still taken from 'In the studio with Emefa Cole', The Goldsmiths' Company.

Prior to my visit to Kumasi, all the literature I consumed on lost-wax casting in West Africa had a tendency to refer to the technique as “primitive”. I was keen to find out more and looked at the various methods used throughout the region, including in Ghana, Ivory Coast and Nigeria (encompassing the Benin, Oyo, Ife and Nok civilisations). I wanted to immerse myself in the actual technique, rather than relying solely on written accounts.

Nana taught me so much, from the coarse clay he started each project with to the charcoal he would pulverise into the smoothest mixture before sculpting the desired form. The laborious nature of the work means that it is vital to have a vast supply of the materials at hand, ready for when needed. I quickly learnt that this wasn’t a technique that could be mastered in a short period of time. The training was intense and learning to work with beeswax on the clay sculpture was far harder than I had read about. As well as learning the traditional methods, with Nana, I have started experimenting with Ferris wax. We are both thrilled with the results so far but have more exploring to do.

Nana believes in passing on his wealth of knowledge, and I am extremely grateful that he has taken me under his tutelage so that I may become a guardian and teacher of this ancient wisdom and technique. This is so much more than a valuable metal. For me, it goes beyond the intrinsic value of gold, beyond the measure of time.